Jason Wee

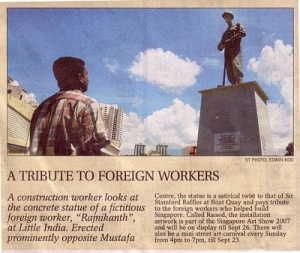

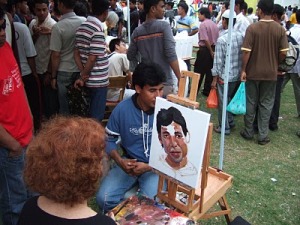

Editors: this essay was originally written for the catalogue of Raised, a mini-art carnival that was part of the Singapore Art Show 2007 [see postscript]. See the Raised blog for documentation by the project artists, Amanda Heng, Shenu Hamidun, Siti Salihah bte Mohd Omar, Sriridya Nair, Nurul Huda Farid, Joshua Yang, Justin Loke and Cheo Chai-Hiang. Pictures here are from the project blog.

When I think about one of the subjects raised by this project, I think about the year 1987 and the state’s previously antagonistic relationship with social justice, especially with regards to foreign workers. In the early hours of 21 May 1987, sixteen people were arrested under an Internal Security Department swoop known as Operation Spectrum. At issue was their alleged foment and participation in a ‘Marxist conspiracy’. In all, twenty two people were detained without trial and, until the last orders were lifted in 1990, all had their movements restricted under various forms of suspension orders and house arrest. Among these men and women The Straits Times had tendentiously called ‘the new hybrid pro-communists’[1] were a number of Catholic church workers working in the Geylang Catholic Centre for Foreign Workers, as well as members of a theatre company that made its name with socially conscious productions such as Esperanza, a dramatization of the lives of Filipina maids working in Singapore.[2]

At this point I could try to exonerate that state action by tracing a history of occasional liberalization in the intervening decades, a trace that is itself only possible if the state is at least willing to retrieve this episode from collective amnesia. But this will not be a bumper-sticker essay, where ‘Things Are Better Now’ trumps ‘What You Don’t Remember Can’t Hurt You’. Instead, I suggest that this figure we call the foreign worker is not here. This is not the same as being invisible. If anything, the migrant workers are all too visible. If Little India is as a Member of Parliament once suggested, so dark you can hardly see or drive through it, perhaps it is because black is an additive consequence of too much colour. And unlike our white-uniform politics, which the state sternly classifies as privy to political parties only, crime and sex suffer no out-of-bound restrictions on commentary. The foreign worker makes an appearance when he or she is victim, witness or perpetrator in misdemeanors and vice, as often as the papers think their readers demand, but not as a person vital to our claims of hospitality, fairness and equality.

To say that the foreign worker is not here is to trace a dispossession. My claim requires a detour through events in Singapore law after 1987 (If you bear with me, the pertinence for art that raises this subject will come through towards the end). Chng Suan Tze, one of the detainees, brought a case against the Minister of Home Affairs in the Court of Appeals. Chng appealed against her re-detention after releasing a press statement detailing the conditions of her detention. The statement includes the following:

Most of us were made to stand continually during interrogation, some of us for over 20 hours and under the full blast of air-conditioning turned to a very low temperature.

Under these conditions, one of us was repeatedly doused with cold water during interrogation.

Most of us were hit hard in the face, some of us for not less than 50 times, while others were assaulted on other parts of the body, during the first three days of interrogation.

We were threatened with more physical abuse during interrogation.

We were threatened with arrests, assault and battery of our spouses, loved ones and friends. We were threatened with INDEFINITE detention without trial. Chia Thye Poh, who is still in detention after twenty years, was cited as an example. We were told that no one could help us unless we “cooperated” with the ISD.[3]

Remarkably, Chng’s appeal resulted in a landmark ruling which found the Minister of Home Affairs providing insufficient evidence for the detention of the accused. This will not be the last time that a member of the judiciary calls for court-admissible evidence in the case of any ISA detention. In his 2003 reading of the case, the former Chief Justice of Malaysia Tun Mohamed Dzaiddin Abdullah saw that the ruling placed the onus on the Executive ‘to justify the legality of the detention of the Appellants by producing evidence that the President acted in accordance with the advice of the Cabinet or the authorized Minister … The evidence required must be cogent as would be admissible in trial’.[4]

By inviting the light of trial to an often secretive process, Chief Justice Wee Chong Jin achieved two outcomes: First, he empowered the judiciary to act as a check on executive decisions regarding national security matters. How the state decides what exactly constitutes national security is outside the purview of the courts, but Wee in his judgment writes in favour of ‘the judicial function of determining whether the decision [to detain] was in fact based on grounds of national security’[5]; Second, the ruling gave detainees a viable channel through the courts to challenge the grounds of their detention, a significant victory considering that their earlier appeals for writs of habeas corpus were dismissed.

The rollback was swift. Within a year, legislative amendments to the Singapore Constitution and the Internal Security Act effectively annulled that ruling. Subsequent legal challenges brought on by a second detainee proved that subjective, discretionary powers of detention have been further ascribed to what is already a powerful executive,[6] and any wisp of a case in court against the grounds for detention evaporated into despair. Throughout this, the application of the rule of law or a respect for due process was never in doubt. Letters of concern regarding the current round of detention prompted a letter from the Ministry of Home Affairs giving reassurance of due process, but due process is so moot it is almost beside the point. We should notice instead the paradox that the legal challenges and appeals suggested in that letter are extra-judiciary. The ISA Advisory Board, while looking like a court of law, able to hear a detainee’s representation and summon witnesses, is patently not a court of law, and the legislation is careful not to name it as such. The Advisory Board operates as an exception from the judicial system. For one, members of the public are not allowed to witness the proceedings. For another, it is not possible to lodge an appeal to a higher court against any ruling by the Board.[7]

In the meantime, the Catholic Center for Foreign Workers closed; the resignation of the head priest broke this camel’s back. Religious organizations were instructed to move away from social justice towards pietistic charity or risk ‘serious repercussions’.[8] Advocacy on behalf of foreign workers was tarred with the perilously red brush of Marxism. Foreign workers are fiercely discouraged from getting organized. In late 1990, Chief Justice Wee Chong Jin retired after 27 years of service to be replaced by Yong Pung How.

An inverse relationship between the situation of the foreign worker and the power of the executive emerges. While one is dispossessed of advocates, the other increases in discretionary power. The image of foreign worker threatens its messengers; sought out as a threat the image emboldens the state. The exceptional power of the state – aided by a law of the ‘special case’, the ISA – conjugates with an attack against an exception, a foreign element, within it. The detainees were allegedly abetting foreign worker unrest as well as orchestrating the whole operation with headquarters in the ivy-laden danger-room known as Oxford University. And is it too crude for my analysis to add that while the foreign worker is currently defined in law by a maximum wage (no earnings more than a stated amount), the executive is measured out by a different cup (no earnings below a top-tier benchmark)?

What we also understand from this bit of legal history is that state action concerns less with securing particular conditions for citizen agency; it is aimed instead at securing the discretionary power of the executive. To raise the subject as this project does is to begin thinking about the conditions of agency. The dispossession affects every citizen, and to the surprise of art practitioners then and now, them too. To say that the ISA is for special cases only is to forget that the law is written to apply to all of us. This law does not discriminate and it does not require detention to be publicly explained. Those with discretionary power decide where and how the shackles fall.

We begin thinking about our positions as subjects – how do we act the way we do, and how are those actions defined for us? Sometimes the knotted paradoxes are the most productive of answers. For example, three persons or more together in public could be charged with illegal assembly in Singapore. Protesters could walk the fine line by setting out in independent groups of two or three. In these cases, a current strategy of protest management involves police linking elbows to isolate an individual protestor. Yet, does not that very act of isolation free the protestor from the charge of illegal assembly? And does the delinking of elbows reconstitute that charge? If so, does it make those police party to wrongdoing?

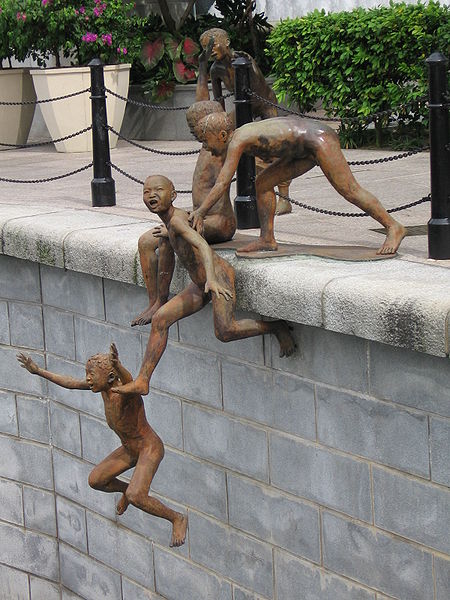

Raising the subject has the double meaning of provoking a topical conversation as well as lifting into view persons and individuals, resurrecting a subject that has not been given a place at the table nor the urgency of being present, here. I thought it was highly suggestive that the schematic drawing in the catalogue is of a platform that is also reminiscent of a coffin The Lazaruses are not here, they are outside the gates. Not that I am intent on only these other people; raising them as subjects raises ourselves as such, a parallelism understood in the end of the movie-musical Love’s Labours Lost directed by Kenneth Branagh. The very moment the foreigners are finally welcomed, they are compelled by circumstance to leave, and it is only at that point these singing and dancing bodies, vectors of lightness, accept guilt and self-consciousness and become subjects. The film ends in the words of the immortal script, ‘you that way, we this way’.

On the other hand, you can retort that these sociological and political ways of talking and thinking ignore the way that those involved in this project are raising the subject as arts, that I have critically elided these projects as art and saw them as ethical-political acts. What I am actually suggesting is that a hybridity is necessary in our approach to these installations, projects and performances, that it is not adequate to resort to either-or, but to grant an admixture without drawing down the divide. I am thinking back to last night’s dinner conversation, when a friend explained how his Peranakan gatherings are coming to question the category of Peranakan as strictly between the ‘pure’ ethnographies of Malay and Chinese, instead choosing to see the term as a mélange of a variety of Southeast Asia ethnicities. Perhaps we could consider that the blurring is not a convenient explanation, but a critical one.

Abandoning continuities from this approach to others in history is not necessary when it is a matter of picking one’s parents, so to speak – Robert Smithson, Littoral and Jean-Francois Lyotard over Anthony Caro, John Currin and Rosalind Kraus. A critic named Grant Kester has called this littoral art, beautifully associating it with the constantly shifting zone between high and low tides. Among other things, Kester asks that we evaluate such art practices on the ‘condition and the character of dialogical exchange itself’.[9] Kester places a great premium on communicative catalysts for change and action. Dialogue, participatory conversations and exchanges are key terms within these practices, and he offers these as one basis for criticizing whether an effort succeeds or fails. To talk about enjoying this art is almost offensive (imagine enjoying a conversation on employer abuse), unless we are thinking of enjoyment along the lines of a demanding empathy, or in Slavoj Zizek’s reworking of the golden rule, of a demand to love your neighbour more than yourself.

I want to say two more things on not being here. In a way, foreign workers are not here because they have never been included even in Marx’s model for economic change. Given that Marx’s proletariat is presumed to be found belonging to various social bodies (the factory, the city, the nation), the foreign worker is excluded from the count for barely registering its presence in any given place; its stay in any given site of production is variable and short, limited by restrictive work permits. Marx would have considered them lumpen, a nebulous neo-class that includes secret society conspirators, prostitutes, service workers, persistent unemployed and beggars.[10] Marx has variously railed against the lumpen for obstructing his revolution and demurred over its significance.

I think that the lumpen is not completely out of Marx’s picture. Instead, I argue that the lumpen is a supplement to social change, a small but crucial nudge to his complicated and often unwieldy systemic theory. Before I provoke an unwelcome red scare with that statement, I will repeat what I wrote recently in the exhibition essay to ‘extra ordinary’. Forget revolution. Even incremental change may be asking too much (I feel like Bart Simpson, writing this on a blackboard for an invisible disciplinarian). But if we are to ask for respect for what is common, shared and public, in other words, for an extra dose of what is ordinary, then the lumpen is one consideration of that ‘extra’, both as excess and sub-par to the original working class. In this case, we can read Marx against himself and see the lumpen as signifying not only the failures of a proletariat revolution, but the foregone possibility of an alternative organizing principle around which a different vision of the future can be vitalized.

Finally, this is me saying as Lucy Davis, the editor of focas: Forum On Contemporary Art & Society, once did. In her essay on the desire for real interactions, Lucy writes of the artist as anthropologist, heading outside the gallery ‘to find and interact with the ‘real’ hybrid’.[11] As she pointed out, it is not more real out there than it is in here. I am not foolish enough to think that through my writing I will raise the subject to a face-to-face exchange with me, or that I could even pin down who a ‘real’ foreign worker is.

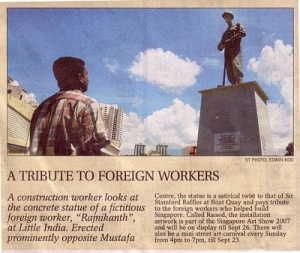

It seems that some of the artists in this project are cognizant of this difficulty of speaking to real subjects. After all, a monument to foreign workers will be presented with inscriptions in a language a great number of them will not be able to comprehend. Two artists re-inscribes the name Raffles as a chain[12] linking persons up in progressive solidarity, thereby presuming the name Raffles to be as free a signifier for us artists as it is for the ‘real’ foreign workers. One crucial decision facing the artists seems to me to be the mode and time of address; addressing the subject directly or by way of another audience, for example, and if the response should be deferred or timely.

Maybe raising the real subject is not the right question to ask anyway, of the efforts in this project, or of this essay. The ‘real’ foreign worker is not here reading this. With a nod to Kester, the questions to ask may be, who is talking (are you talking to them), and who is talking to whom (are they talking to you)?

Notes

[1] ‘Marxist Plot Uncovered’, The Straits Times 27 May 1987.

[2] Chris Lydgate, Lee’s Law: how Singapore crushes dissent (Melbourne, Scribe Publications 2003), 200.

[3] Francis Seow, To Catch A Tartar, (New Haven, Monograph 42, Yale Southeast Asia Studies, 1994), Appendix 1.

[4] Tun Mohamed Dzaiddin Abdullah, ‘National Security Considerations under the Internal Security Act 1960 – Recent Developments’, Malaysian Law Journal. First presented at a conference on “Constitutionalism, Human Rights and Good Governance” at Kuala Lumpur on 30 Sept to 1 Oct 2003.

[5] Chng Suan Tze vs. Minister of Home Affairs, Singapore Law Report 132, C.A.

[6]Teo Soh Lung vs. Minister of Home Affairs, Singapore Law Report 40, C.A.

[7] Internal Security Act 8B(2).

[8] The Straits Times quoted in Chin Kin Wah, “Singapore: Threat Perception and Defense Spending in a City-State,” in Defense Spending in Southeast Asia, ed. Chin Kin Wah (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1987), 246.

[9] Grant Kester, ‘Dialogical Aesthetics: A Critical Framework For Littoral Art’, Variant 9.

[10] Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, in Marx & Engels Collected Works: Volume 10 (Moscow 2005).

[11] Lucy Davis, Natural Born Vandals (Or The Desire For Real Interactions With Real People), focas: Forum On

Contemporary Art & Society No 1 Jan 2001, 130.

[12] See chain of equivalence in Ernesto Laclau, On Populist Reason, (Verso, London 2005).

Postscript

An essay I wrote for Raised, a festival revolving around foreign workers, has been pulled from publication by National Arts Council. Raised is a major component of the Curating Lab, part of this year’s Singapore Art Show. 8 artists are involved, and three of them corresponded with me as I wrote my essay – Amanda Heng, Cheo Chai Hiang and Justin Loke.

It began early last week, when NAC called for a meeting regarding the publication of the catalogue. It was originally going to include my essay, artists’ interviews as well as images. Amanda and Chai Hiang were called, but I was strangely omitted. Lim Chwee Seng, Phillip Francis, Director and Assistant Director of visual arts in the Council were present. Amanda and Chai Hiang were told that the essay cannot be published. Amanda had asked if the essay could be published if they suggested areas for rewrites, but the directors were firm on their request for no rewrites, but no publication. According to Amanda, they offered a few rationales to her and Chai Hiang, one being that a single catalogue essay will overwhelm any other interpretation of the artists’ work. Amanda, that dear woman, replied that speaking as one of the artists involved, she has no fear that Jason will overwhelm her work. Another rationale was at five pages, my essay was too long in comparison to the shorter artists’ interviews, but again, they were firm on suggesting no rewrites.

When I’ve gotten word of the meeting, I called Phillip up to talk over a coffee. Phillip was careful to avoid framing the removal of the essay from publication as censorship. Whether he is reflecting his boss’ opinion, or his own, I cannot tell. He says that NAC will look for alternative platforms to place the essay.

A few questions came to my mind. In deciding between publication platforms, does Chwee Seng and Phillip have some kind of division between publics, between a critical one and a non-critical one, for example, or between a populist readership and a marginal one? And what does pulling the essay the week before the Art Show opens say about the possibility of re-publication? Also, it is hard for me to determine the level of sensitivity that the two directors have taken issue with. Is the essay threading on sensitive territory because I connected the ramifications from 1987’s Operation Spectrum to the contemporary engagement with foreign workers as a social cause? Or is it because I footnoted Francis Seow? Or is it because I discussed the dreaded Internal Security Act? Or is it simply because I suggested possibilities of seeing socially engaged work as art, where the social engagement is evaluated as a crucial criteria of the work’s artistic success? Finally, since my writing is part of the meeting’s agenda, isn’t it professional courtesy to call me to the meeting?

That is the problem with bureaucratic positions that suggests ambiguity in place of censorship. I understand the desire for wiggle room, but I also wonder if it might be better for the council to hold a press conference for every future time they decide to withdraw a license, pull a publication, cut lines or images. Publicly announce the decision and the rationale. If there is no rationale, just say exactly that. At least it acknowledges how the requirement for justification is, in reality, low, and it preempts journalists going to artists to ask difficult questions that the council might be unhappy about.

On hindsight, looking at this from 2010, the offer to find alternative publication is a deceptive misdirection. I have not received any offer in the intervening period to re-publish, and I have not received any apology for they not being able to find opportunities to do so

Jason Wee is an artist and a writer. He also runs Grey Projects, an alternative arts project space, www.greyprojects.org

Read Full Post »